There are a staggering number of people in the U.S. suffering from hoarding behavior. Individuals engage in excessive accumulating or have difficulty letting go of items, sometimes so severe that it interferes with normal activities of daily life. Rooms are no longer usable for their intended purpose, we see dining rooms cluttered with belongings not meals or tubs holding clothes not bathwater. Statistics estimate that 15 million people are dealing with this issue. In Philadelphia, the estimate is 31,000 -77,000.

A cleanout is the method most municipalities use to deal with hoarding. Reducing the volume of clutter to safer levels is thought to alleviate the problem and support the person. The reality is, without treatment and support for the individual, the rate of recidivism after a cleanout is nearly 100%. With the high cost of cleanouts and low rate of return, cities are beginning to pay attention to research findings.

Thanks to the research of doctors Frost, Steketee, Tompkin and Tolin, we are now understanding that cleanouts are “stuff-centered” and don’t address the issues buried below the surface. Simply removing clutter without addressing the underlying issues illuminates the reasons for high recidivism rates after cleanouts. This research is stimulating new intervention models. Being “people-centered” is the common theme. They each involve the person with hoarding behavior as key to the solution. Given that 92% of individuals diagnosed with Hoarding Disorder also have another co-occurring disorder, there is no one set solution.

The work is personalized and takes keen listening skills, creativity, flexibility, patience, and lots of compassion. Instead of focusing solely on the volume of clutter, a spotlight shines on the safety and well-being of the individual while working to reframe old thoughts and beliefs to reduce the dependence on acquiring and saving. There is no magic pill. Everyone involved understands this disorder has deep roots; the process takes time and relapses are as common as seen with over eating or drinking.

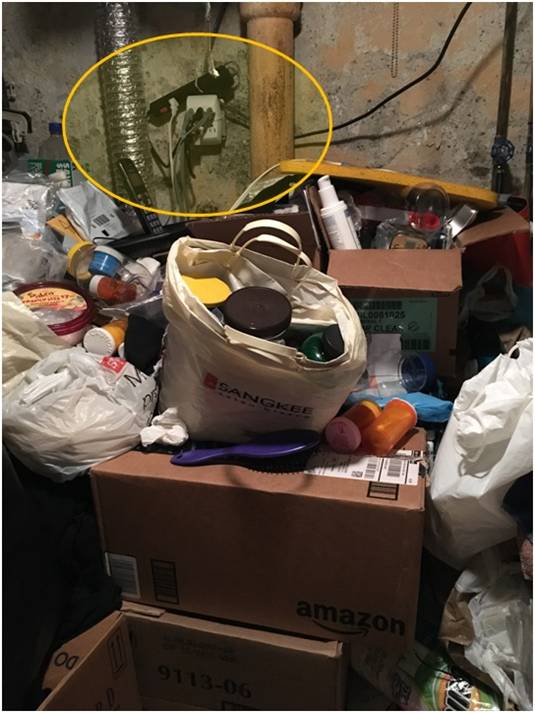

One of the new models is Harm Reduction (HR). Its goal is to reduce the risks associated with hoarding. Instead of talking about the “stuff” to get rid of, it asks the question, “How do we keep you safe in your home and maintain clear access for emergency staff and equipment if the need ever arises?” The (HR) process provides a support person that works with the individual identifying key health and safety concerns in the home. They also serve to document goals to alleviate the issues. From this information, they design and implement a strategy to address these issues over time.

One such organization that has adopted this (HR) model is the Philadelphia Hoarding Task Force (PHTF). The Task Force is a coalition of organizations that seek to improve outcomes for people who hoard while balancing the rights of the individual with the health and safety needs of the community. PHTF is introducing service providers to this model as a way to circumvent the costly and catastrophic consequences often seen with cleanouts and instead, create favorable long lasting results.

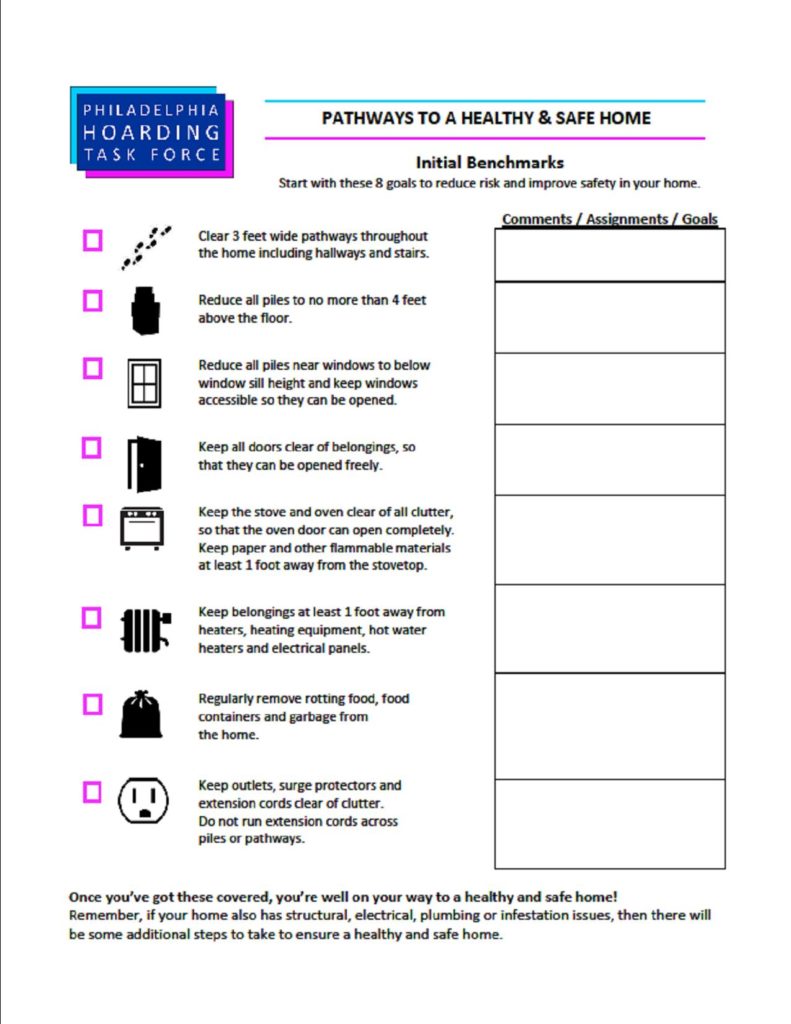

Consulting with its members from Licensing and Inspections and the Fire Department, PHTF has come up with 8 Benchmarks to follow to create healthier, safer homes. These benchmarks provide specific measureable goals that support, guide, and unify everyone involved. They address potential hazards regarding fire, tripping, limited access in or out of the home for the individual, emergency personnel and their equipment, avalanches, health issues and infestation. The benchmarks are as follows:

As a Productivity and Organizing Professional, I am preoccupied with effective ways to calm the chaos in people’s lives. When I saw this short 3 minute video, I thought it was a great demonstration of how disorganization and chaos unfold without notice while everything falls into disarray and nothing gets done. If you can relate, then here are 8 easy suggestions to help calm the chaos in your life.

As a Productivity and Organizing Professional, I am preoccupied with effective ways to calm the chaos in people’s lives. When I saw this short 3 minute video, I thought it was a great demonstration of how disorganization and chaos unfold without notice while everything falls into disarray and nothing gets done. If you can relate, then here are 8 easy suggestions to help calm the chaos in your life.

In the video, the chaos began when the actor put her keys down on the table to pick up the mail. In that moment, she lost her connection to her keys and shifted her attention to the mail. She no longer had a cognitive or tactile association with the keys. Her connection transferred to the mail instead. That loss of connection was played out over and over in the video as the chaos unfolded. She lost her awareness of her checkbook, the remote, her glasses and, ultimately, her ability to complete a task with ease.

If you must pick up the mail before putting your keys in their designated spot (create one if you don’t already have one), hold onto the keys. That is, stay connected to the keys while you are sorting the mail. Then, when your attention turns away from the mail, your keys will be in your hand as a tactile reminder that the task of putting your keys away is not complete.

If the actor had held onto her keys while she sorted the mail, or her checkbook while she walked to her desk and then to the kitchen with her warm Coke, both her keys and checkbook would have signaled to her that the task wasn’t done, and ultimately reduced the number of incomplete tasks left in her wake.

The video shows how random the actor moved from one task to another. What caught her attention became the next priority without thought or question. If this feels familiar, try counting to 8 slowly before you move from one task to another. This allows time to slow down and contemplate which task is more important and should be done first.

If the actor took time to stop and count to 8 before shifting from one task to another, she could have made conscious choices to either stop what she was doing and move to another task or not. Having time to choose lends itself to better outcomes and less chaos.

Taking on and practicing one or more of these suggestions, over time, will strengthen your ability to calm the chaos and be more effective, efficient and productive.

In oftentimes challenging situations loaded with minefields and judgments, have fun trying different ways to “stay connected” to a task. So I can’t forget things while I’m working, I wear a “task pouch” around my waist with pockets like a carpenter’s tool belt. In it is everything I need at my fingertips: phone, markers, scissors, and a pad and a pen to capture tasks to do and things to remember. This is my way of keeping worry and brain chaos at bay.

Be compassionate with yourself when taking on new practices. Misses and backsliding are common during any learning process.

If you find you need support, new ideas, a coach or a cheerleader as you take on new practices, give one of us a call. We would love to assist you in calming the chaos in your life!

At different times in life, one finds oneself faced with the task of making life-altering changes to pave the way for new possibilities. As an organizer, I have the privilege of being with clients as they journey toward a new life and new possibilities. An inspiring vision is their guiding light and a tool box of new questions is their rudder, navigating them toward their goals and aspirations.

At different times in life, one finds oneself faced with the task of making life-altering changes to pave the way for new possibilities. As an organizer, I have the privilege of being with clients as they journey toward a new life and new possibilities. An inspiring vision is their guiding light and a tool box of new questions is their rudder, navigating them toward their goals and aspirations.

Inspired by speakers Joshua Millbum & Ryan Nicodemus, “The Minimalists”, and Marilee Adams’ book “Change Your Questions, Change Your Life”, I have been exploring the notion that one could change one’s life, its patterns, habits and outcomes simply by changing the questions we ask ourselves. Can it be that simple?

When you think about it, questions illuminate:

Questions shed light on, and offer a deeper understanding of, the choices we make and why. Dr. Adams says, “Our behavior follows our questions” and “new questions shape and direct new behaviors.”

When I began questioning myself about the “stuff” in my life, I noticed there was an innate, underlying meaning I had given to each item that was affecting my decision-making process. During one of my closet purging events, I began to hear the meanings I had assigned each item. Slowing down and listening carefully, I could hear myself arguing for each item and justifying why things should stay, saying:

In other areas of my home and my clients’ homes, I see items being kept for fear that the memory will be lost forever if not saved. Text books, research papers and thesis notes are symbols and trophies of accomplishments and successes representing a former self and held for posterity. Items that have recognized value are held to say something about us even though we don’t like, appreciate or use them.

Why do we give so much meaning to our stuff? Who knows? What I’ve noticed is that when the meaning we give to items remains unexamined and undistinguished, the more likely they are to stay on our shelves versus leave to create space in our lives. Asking rigorous questions and listening intently for the meaning we give to items offer us new interpretations and perspectives, and the freedom to let go.

Questions I like to ask are:

Last week I spoke to someone who was facing a plumbing crisis but needed to declutter large areas before the repair work could be done. Questioning himself, he began to uncover that he was, as he called himself, “Mr. Someday.” Things he acquired and saved were for someday. When he saw something, his question was, “How can I use this, someday?” It’s not such a bad question once in a while, except what he was now facing was all the “someday” projects that never happened and instead were impeding the plumbing repairs. Armed with both a new vision to say goodbye to “Mr. Someday” and new questions to shape his actions moving forward, he was off and running to change his lifestyle and life.

How might life be better if we owned less stuff?

The Minimalists say, “Life can be richer with less stuff.” Dr. Adams’ asks, “What new questions can take us there?”

If letting go to reduce the amount of stuff in your life is your mission and you need help along the way changing your questions to change your life, find an organizer in your area. We would love to support you.

Click on the title above to learn more about the featured author.

These past few weeks, I have been grappling with a kind of spiritual awareness which continues to unearth and challenge the way I perceive life. I find myself reflecting on the way I think and feel, and also upon the actions I do or don’t do.

These past few weeks, I have been grappling with a kind of spiritual awareness which continues to unearth and challenge the way I perceive life. I find myself reflecting on the way I think and feel, and also upon the actions I do or don’t do.

In wanting to explore this new era of enlightenment, I took Eckhart Tolle’s book, The Power of Now off my shelf. Its content is unwaveringly dense, often leaving me exhausted by concepts too thick to conquer. Though the pages have barely been touched, the title, “The Power of Now” remains ever present to me: challenging me, questioning me, and inspiring me.

Life lived NOW means being present to the opportunity of this moment in time. This moment is the opportunity to experience exactly what is happening, and not what I/we should or could be doing…nor the eight tasks work expects done simultaneously and seamlessly. On the other hand, the familiar sentiment, life lived “Someday, One Day” clouds being present to the gifts of now. A “Someday, One Day” attitude often creates log jams and stagnation in our physical, emotional, and spiritual space. Procrastination goes hand-in-hand with life lived from a “Someday, One Day” perspective.

Being present to NOW fosters gratitude, calmness, peace and stillness…much like the breath we are asked to be present to in our meditation or yoga practices. And in this state of NOW, life flows. Action is second-nature; it is real, purposeful, and natural. It is not sabotaged by “Someday, One Day’s” indecisions, doubts and postponements. Lightness, awakenings, and insights are encouraged by the presence of “NOW” thinking. Fear of change, the unknown, or something different, keeps the “Someday, One Day” card in our hip pocket ready to be played when life feels uncomfortable.

Eckhardt Tolle said, “Some changes look negative on the surface but you will soon realize that space is being created in our life for something new to emerge.” I see this played out time and time again in my own life and in the lives of my clients. Taking on “Someday, One Day’s” mantra of “later, later, later” and actually getting started now creates oceans of energy. Physical spaces are transformed uncorking the damned up to-do’s, intentions, goals and aspirations allowing life’s energies to flow again. Frequently, at the end of a session, clients feel lighter, freed up and elated as the stagnate piles and clutter dissolve into organizational bliss.

Eunice S. Carpitella, Executive Coach & Leadership Development Consultant of Transformative Dynamics, said, “LATER” is the enemy to living a fulfilled, satisfying and rewarding life. It’s always convincing you that whatever needs to be done will somehow be improved by waiting.”

Werner Erhard lightened up this dilemma for me saying, “Thinking about ‘it’ leaves you with more thoughts and older.”

Life is passing by and with it, those precious moments of NOW’s gifts. Moments are accumulating into days, months and even years. We yearn to live our dreams, not the reasons why not. “Someday, One Day” is the status quo and “later, later, later” its hypnotic song. Overcoming “later’s” mantra takes motivation, drive, a push, and support fuelled by a vision to let go of “Someday, One Day.”

Bringing order to chaos and freedom and ease to life is what Professional Organizers love to do. Call an organizer when you need a gentle nudge, a kick start, a fresh set of eyes or a partner to drive away the “Someday, One Day” blues.

Cause a life you love, lived joyously in the presence of NOW — moment by moment.

Embrace The Power of NOW!

I read an interview with Michael Jensen, Emeritus of Harvard Business School entitled, “Integrity: Without It, Nothing Works,” a bold title, that peaked my interest. He really made me see that if I got in sync with the “Law of Integrity,” I could tackle those areas in my life — where I feel stuck — with greater ease. I could create workability where it is lacking and increase my productivity and performance tenfold just with a little practice.

Before I read the interview, the word integrity, made me think of “integrity” as a virtue; it is good to have integrity and it’s bad not to. The article helped me see that being caught up in the good / bad, right / wrong characteristics of integrity hides its relationship to workability and performance. Jensen makes the case that “as integrity declines, workability declines, and when workability declines the opportunity for performance declines” as well. He calls it the Law of Integrity.

Think of the spokes on a bicycle. If I remove spokes from the wheel, the integrity of the bike is increasingly diminished with each spoke I remove. As the integrity is more and more dimished, the wheel becomes less and less workable: its performance is ultimately compromised.

Jensen gives an example of how things that lack integrity affect our lives. Think of your car. When you don’t manage its maintenance, parts of the car can begin to wear out, run less efficiently, or break. The car becomes unreliable which makes you late for work, late for meetings, maybe even late to pick up your child at school. The “out-of-integrity” of your car creates a lack of integrity in your life that produces all kinds of fallout. Over time, you begin to show up as unpredictable, unreliable and untrustworthy, to your work associates, family members, and yourself.

The effects of the “out-in-integrity” behavior in our lives mostly go misidentified, unnoticed, and unacknowledged by us and others. We could simply say, the issue is with the car. However, if we look at integrity as defined in the article as “a state or condition of being whole, complete, unbroken, unimpaired, sound and in perfect condition,” then the condition of my car directly provides “actionable access” that leads to opportunities for workability that enhance my ability to perform in life. With this model of integrity, the breakdown with my car illuminates the pathway or actionable steps I can take to create, maintain and restore integrity. This, in turn, gives me direct access to maximum performance in all areas of my life.

Fundamental to the Law of Integrity is honoring your word with yourself and others. More specifically, it means:

If we faithfully manage our integrity with ourselves, with the groups we are involved with, and the organizations that are important to us, Jensen explains, over time, “it enriches the quality of one’s life.” Effectiveness, workability, and increased performance are all a by-product of this model of integrity. He says, “People fail to link the difficulties in their lives or in their organizations to out-of-integrity behavior. The increases in performance that are possible by focusing on integrity are huge.” In his own company, after three years of implementing this Law of Integrity, Jensen saw a “300% increase in output, with essentially no increase in inputs.”

Michael Jensen makes a convincing case for integrity’s critical link to performance. Think about areas in our lives that don’t work (our homes, our work environments, our healthcare system, the financial industry, our political system). What would be possible if we, as individuals, in our society took on the “Law of Integrity” in those areas where we feel stuck, life feels unworkable and productivity needs a boost!

Wow, that would create a new future for all of us!

Click on the title above to learn more about the featured author.

The Philadelphia Hoarding Task Force, a coalition seeking to improve the outcomes surrounding hoarding issues, hosted a hoarding intervention workshop led by Jesse Edsell-Vetter. Jesse presented an innovative intervention model that he has developed and implemented with an impressive 98% success rate. The key to his model is the shift of focus from the “stuff” to the person.

In the past, Jesse, a Case Management Specialist with the Metropolitan Boston Housing Partnership, had used a common approach when dealing with hoarded homes. He would explain the health and safety issues and cite the code violations that had to be resolved to prevent eviction. After leaving the person alone to address these issues, follow-up meetings predictably showed little-to-no progress. A clean-out was the inevitable next step, costing an average of $10,000. Over time, Jesse observed the homes return to their hoarded state. Focusing solely on the clutter has proven to be extremely costly and unsustainable as a treatment option. Beyond the monetary cost, the emotional trauma is also a factor. In one tragic example, a family returned to their home after the clean-out and committed suicide.

In response, Jesse shifted his approach from focusing on the “stuff” to focusing on the person: who they are, their commitments, their struggles and what moves them. For the majority of us, life’s challenges leave scars and hurts that dissipate with time. For people with hoarding behavior, woven in the items they hoard are their scars on display for all to see and judge. While a clean-out removes the “stuff,” it does nothing to unlock the stories and hurts interwoven in the piles. Jesse’s model, in contrast, coaxes these stories out with respectful, compassionate and nonjudgmental interactions emphasizing the human side of the clutter, lessening the grip of extreme hoarding habits.

During the workshop, Jesse shared a case study about Bob, an elderly man challenged with health problems, living alone, facing eviction, and surrounded by paper piles, some as high as seven feet tall. Rather than mandate compliance to codes and leave Bob alone to manage his stuff, Jesse explained the safety requirements to Bob and asked how he could help. Jesse gained Bob’s trust with empathic statements like, “I worry that X” and “I am concerned because Y.” As Jesse rolled up his sleeves and sorted through the piles with Bob, he asked questions such as, “Tell me about your X” or “Tell me about these papers I see.” This technique of “curious questioning” revealed Bob’s vulnerabilities (mental and physical health, traumas, and family history), his cognitive processes (problem solving, attention, and executive functioning skills) and his core beliefs (values, responsibilities, and how he sees his place in the world). Jesse learned that Bob came from a very religious family. Three of his sisters were nuns, and he himself had wanted to be a priest. Struggling with his sexuality, at age 20 Bob told his family he was gay. He was then shunned by his family and his religious community. Fast forward from that time in the early 1960’s to the present day, Bob’s apartment was a manifestation of that devastating loss. One item Bob hoarded was church bulletins. He attended church services every day, each day taking copies of the bulletin with the intention of sharing them with others. From the overwhelming piles, it was obvious though that this rarely happened. Using a team approach, a cornerstone of his intervention model, Jesse invited Bob’s priest to collaborate. Seeing how committed Bob was to his religion, the priest asked Bob to assist him in providing communion to people who were unable to attend church. In that moment, Bob recovered his purpose in life and adopted a healthier expression of his deep connection to his church and community.

Bob’s story illustrates the human side of Jesse’s 98% success rate, showing what’s possible when we leave our judgments at the door, stop addressing the person’s “stuff” and instead, unlock the stories and hurts buried in the hoarded piles. When intervention models lead with the threat of a clean out, walls go up, but, as Jesse has shown, when the intervention is infused with respect, non-judgment, curious questioning, statements of concern, clearly articulated expectations and actions, motivation and genuine praises for milestones met, partnership and collaboration becomes possible and the work of letting go and healing begins. In Bob’s case, when the priest invited Bob to help him, Bob was able to connect to his life again and the importance of his “stuff” could take a back seat.